Alternative Fuels Part 5: Dropping bio in oil

The fifth and final piece of this alternative fuels series puzzle brings us to biofuels. It is a broad term that can be anything biomass-derived but which is generally taken to mean FAME or HVO as marine fuels.

Biofuels have similar combustion performance to oil-based fuels and can be consumed by ships without substantial engine or vessel modifications.

Demand has started picking up over the past two years. Sales of bio-blended fuel oils and distillates nearly quadrupled on the year in Rotterdam to 193,000 mt in the third quarter last year. That was more in a single quarter than the 140,000 mt of biofuel blends sold in Singapore across the whole of 2022.

But demand is reportedly on the rise in the world’s biggest bunkering hub, too, and could easily grow to surpass Rotterdam’s volumes now that major suppliers like Vitol Bunkers, Chevron, ExxonMobil and TotalEnergies have put their weight behind it.

Singapore’s port authority has devised a framework for licencing bunker suppliers and a provisional quality standard that requests bunker suppliers to supply International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC)-certified biofuel.

Sustainability and emissions

Crop-based biofuels are widely considered unsustainable as they can compete with food, lead to deforestation and generally take up large areas of land. Their environmental credentials might therefore be just as poor or even worse than today’s conventional oil-based fuels.

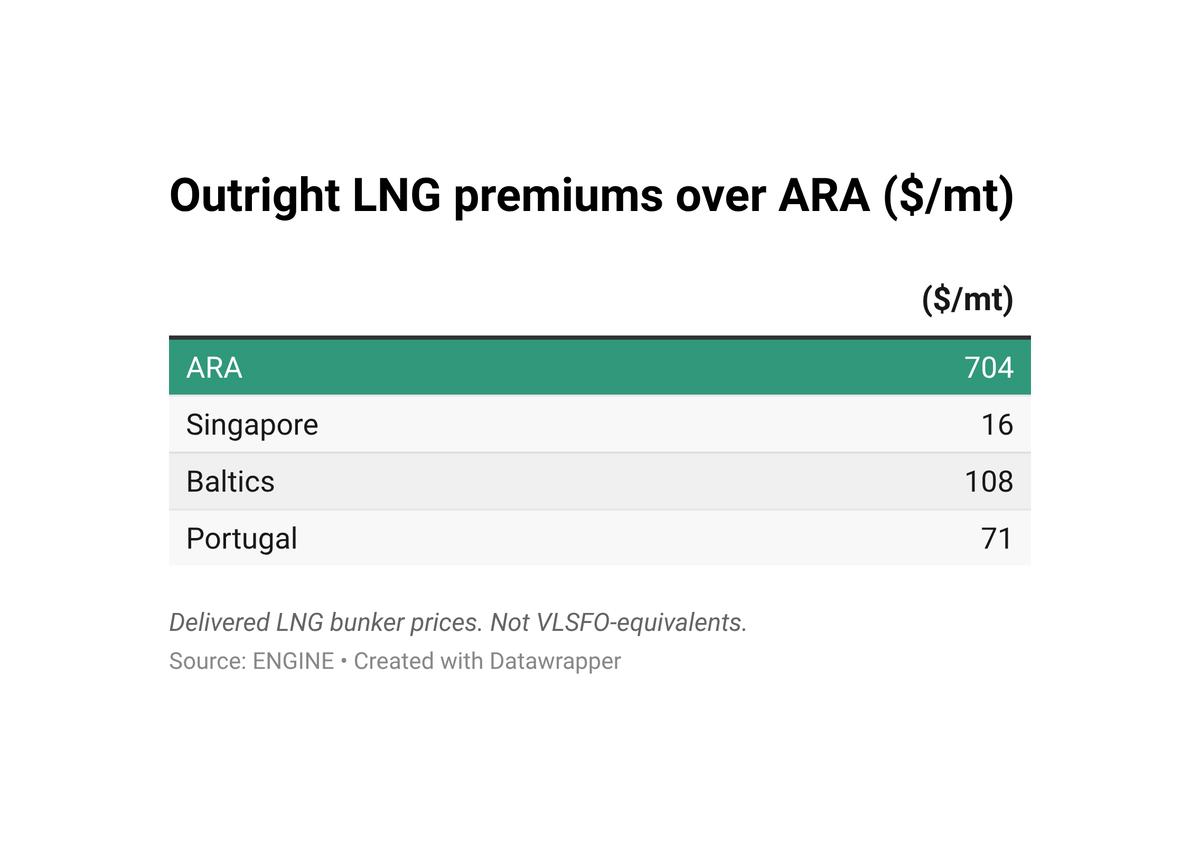

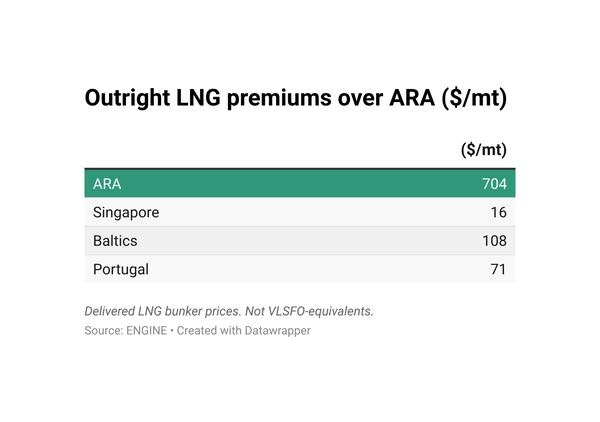

CHART: Lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions (100-year global warming potential) of alternative liquid marine fuels and feedstocks. ICCT

CHART: Lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions (100-year global warming potential) of alternative liquid marine fuels and feedstocks. ICCT

On a lifecycle assessment basis, waste-based biofuels typically come out much better than oil. They can have 70-100% lower greenhouse gas emissions than marine gasoil (MGO), a 2020 study by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) found.

Dutch biofuels supplier GoodFuels, for example, has claimed its 100% biofuel (B100) can reduce a ship’s CO2 emissions by 78-90% on a lifecycle basis. It has also started to use isotopic tracers in biofuels to track and verify if the fuel has been diluted or tampered with during any stage of the supply chain. It can further be used to ascertain if the fuel is completely composed of biofuel or blended with conventional marine fuels.

Drop-ins

In Fujairah and the ARA, biofuel blends can easily go up to B30 (30% biofuel, 70% oil) and occasionally B50 and B100. There are not yet any regulatory incentives to run vessels on B50 and B100. It’s rather for environmental, reputational or operational experience-gaining reasons that owners go pure biofuel.

More often than not biofuels are dropped into VLSFO, and to a lesser extent HSFO, ULSFO, MGO or MDO. Many bunker suppliers in major ports seem to at least have dabbled into biofuels by now, and some have gone all in to capture what could quickly grow from a very niche part of the bunker fuel mix to a serious chunk.

But how far can it go?

World Bank research report argued that: “Without a breakthrough in aquatic biomass production, biofuels (for example, biomethanol, bioethanol, or liquefied biomethane) are likely constrained to play a rather minor role in shipping’s future energy mix.”

This calls into question whether there will be enough sustainable bio-feedstock available to scale biofuels bunker consumption more widely across the global shipping fleet, especially when considering price-pressure and competition from other sectors.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) recently warned that insufficient production capacity and a lack of feedstocks is likely to end in a biofuel supply crunch over the next five years.

Initially, biofuels demand was driven by the road transport sector, with the EU as an early adopter of a minimum biofuels target of 2% by the end of 2005. That mandate has since been broadened several times to now include a target of 14% of energy in road and rail transport to come from renewable sources by 2030. As more combustion engine vehicles are replaced by electric ones, more bio-feedstock could be freed up for shipping and aviation in Europe and elsewhere.

Except for the heights of the Covid-19 pandemic, when air travel was restricted and many planes were grounded, jet fuel has historically been priced at sustained premiums over bunker fuels. If this trend continues, with airlines able to pay more for fuel thank shipowners, the bunker market could find itself outcompeted on price for bio-feedstocks, too.

HVO vs FAME

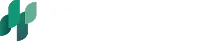

Hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) looks like a particularly expensive option, coming in at a premium of $1,850/mt above ICE Gasoil on a FOB ARA basis. By comparison, fatty acid methyl ester’s (FAME) premium over ICE Gasoil has ranged between $613-762/mt so far this year. That is still prohibitively expensive in a pure cost perspective and will put a lot of shipowners off steady consumption of high volumes.

In addition to price, there are other key differences between FAME and HVO, particularly when it comes to their energy contents, how well they perform in colder climates and their long-term storage potential.

HVO typically has similar or even higher energy content than marine fuel oils and gasoil. It also outcompetes FAME by around 10% on this metric, giving owners more bang – but as we have seen – for a much higher buck.

FAME’s cold flow properties can be a cause for concern, as waxing can occur during winter in colder regions. This can to some extent be mitigated by heating it – as with viscous residual fuel oils. But then you can run into problems with oxidation, clogging and potentially corrosion in ship engines.

Because FAME naturally attracts water, microbes can start forming, oxidation can occur and the shelf life of the fuel could be cut short. HVO is more stable by comparison and does not face these issues.

PHOTO: B100 biofuel produced by Neste being delivered to NYK Line's tugboat - the first B100 trial in Japan. NYK Line

PHOTO: B100 biofuel produced by Neste being delivered to NYK Line's tugboat - the first B100 trial in Japan. NYK Line

“There is zero risk of quality deterioration or microbial growth,” Neste has said about HVO. The Finnish energy firm hydrotreats low quality waste and residues into HVO that it claims has the same quality as a finished product every time. This is because unlike FAME, HVO doesn’t go through transesterification – a reaction between oil or fats with methanol to produce the methyl esters in FAME that are prone to water-absorption.

ISO specification 8217:2017 includes a provision for up to 7% FAME by volume in most marine distillate grades. But FAME has been blended with bunker fuels at much higher ratios in B50 and B100 trials. HVO can easily go up to B100, but again, at a steep price.

Thermochemical candidates

The Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping (MMMCZCS) has disregarded both FAME and HVO altogether, arguing that despite being available commercially today, a lack of feedstock and “intense” competition with road transport and aviation for the feedstock that is produced will hold them back from making a serious mark on shipping’s decarbonisation efforts.

Instead MMMCZS highlights so-called bio-oils made from pyrolysis or hydro-thermal liquefaction. But unlike HVO and FAME these methods are currently technologically immature and only performed at a few small-scale production plants.

Demand projections

So, considering estimates that around 10-12 exajoules (EJ) are needed to power the global shipping fleet today, how much of that energy can biofuels realistically provide?

First-generation crop-based biofuels production is only expected to grow by 5% by 2030, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and Food and Agriculture Organisation. Second-generation waste-based biofuels could theoretically fuel the entire global fleet, but only if it was not competing with other sectors for feedstock.

CHART: Global bunker fuel mix projections for 2050. International Chamber of Shipping

CHART: Global bunker fuel mix projections for 2050. International Chamber of Shipping

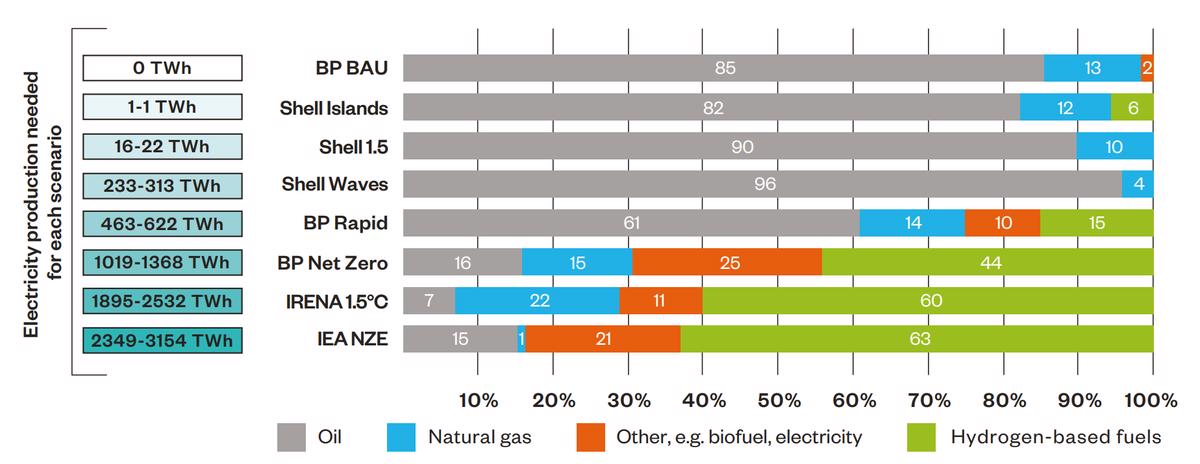

Projections vary greatly for how big biofuels’ piece of the bunker fuel pie will be in 2050 in a net-zero, Paris Agreement-aligned scenario. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) thinks biofuels will make up 11%, and that a bigger 11% share will be taken up by LNG. BP and the IEA are more optimistic about biofuels and project they will make up 21% and 25%, respectively.

Looking at Rotterdam’s bunker sales, the share of fuel oils and gasoil with biofuel blended into them more than doubled from 3% in 2021 to 7% in the first three quarters of 2022. In the projections laid out by BP and the IEA there will be significant growth potential for biofuels in bunkers in Rotterdam and other ports.

IRENA’s projection leaves less room for growth in Rotterdam - if we assume that it is representative of the global average. Singapore has comparatively much greater potential for biofuel bunkering growth as only 0.29% of bunkers sold last year was blended with biofuels.

By Erik Hoffmann

Please get in touch with comments or additional info to news@engine.online