IMO’s proposed fuel standard will promote LNG consumption on ships – Maersk

The current proposal for a GHG Fuel Standard at the IMO “heavily” favours LNG, argued Morten Bo Christiansen, head of energy transition at Danish shipping firm A.P. Moller – Maersk, in a social media post.

PHOTO: Maersk-owned container ships. A.P.Moller-Maersk

PHOTO: Maersk-owned container ships. A.P.Moller-Maersk

Christiansen claimed that the proposed framework will effectively make “the principle of pay-to-pollute the financially most attractive strategy for most shipping companies” in the coming decades.

The majority of ratifying countries support implementing a greenhouse gas (GHG) fuel standard (GFS) as a technical measure under the IMO’s mid-term measures.

A recent UCL report indicates that the latest Chapter 5 draft outlines a requirement for every vessel to meet an annual GHG emissions intensity target based on onboard energy use. This target could be calculated on either a well-to-wake or an adjusted tank-to-wake basis, both of which include upstream emissions.

The proposed GHG intensity caps could require a 5.8–10% reduction by 2030, increasing to 65–68% by 2040, or a 12–24.5% reduction by 2030, rising to 67.5–78.5% by 2040.

Compliance would be assessed by comparing a ship’s attained greenhouse gas fuel intensity (GFI) with a specified GFI standard. The GFI measures the total GHG emissions released into the atmosphere based on the amount of energy used by a ship and is expressed in grams of CO2-equivalent per megajoule of energy (gCO2e/MJ).

Non-compliant vessels could offset their GFI deficit by purchasing credits from overperforming ships, buying reserve units from the IMO or paying a surcharge.

Unintentional advantage for LNG

Maersk’s Christiansen warned that the proposed calculation method creates a “significant discrepancy” between actual GHG emissions savings and the assigned deficit for onboard fuel use.

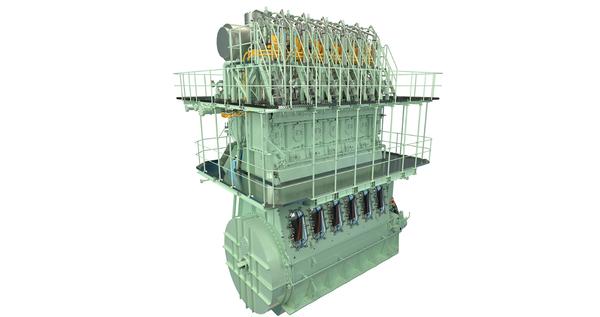

The discrepancy can arise from the type of engine used.

“While LNG burned in the right engines can deliver a GHG emissions reduction of up to 19% vs traditional fuel oil, it will get a disproportionate financial benefit far exceeding what is merited by this reduction,” he argued.

In this case, the "right engine" likely refers to a diesel slow-speed engine, which has a methane slip of 0.2% - the lowest among LNG dual-fuel engines. In contrast, a medium-speed Otto engine has the highest methane slip at 3.1%. Since most LNG-capable vessels in operation today are powered by either of these two engine types, the variation in emissions accounting will be substantial.

A dual-fuel containership burning LNG in a diesel slow-speed engine could generate a deficit of only 0.83 units, compared to 1.58 units when burning VLSFO, Christiansen noted.

This could result in a cost advantage of approximately $300 per forty-foot container on a voyage between Asia and Europe.

Christiansen also highlighted that LNG’s financial advantage will be further reinforced by the limited availability of liquefied bio- and e-methane, which are considered greener alternatives to fossil LNG.

As a result, the proposed framework could negatively impact demand for zero-emission fuels like blue and e-ammonia, as well as bio- and e-methanol and potentially undermine the green fuel transition.

“Even adding a reward for low-emission energy sources will not change the highly beneficial business case for LNG versus low-emission fuels,” he said.

To address these concerns, Christiansen suggested that deficit units should be calculated directly based on actual emissions reductions and that the accumulation of surplus compliance units should be limited to one year.

In addition, “a levy could mitigate the inherent fuel standard flaw, yet it would have to be substantial,” he concluded.

By Konica Bhatt

Please get in touch with comments or additional info to news@engine.online