INTERVIEW: Hydrogen fuel cells to power short-sea shipping before scaling to deep-sea from 2028 and beyond - TECO 2030

We are confident that fuel cells will initially power zero-emission vessels on shorter distances in coastal areas, like the Baltics and the UK, says Tore Enger.

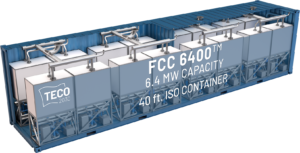

PHOTO: TECO 2030's fuel cell systems range between 1.6-6.4 megawatt (MW) capacity, with the larger 6.4 MW system filling up the space of a 40-foot ISO container. TECO 2030

Enger is the chief executive of TECO 2030, a company set up in 2019 to produce hydrogen fuel cells for vessels. TECO 2030 spun out of Enger’s marine technology and services company, TECO, which he founded in the mid-1990s.

In the second half of the 2010s, TECO set its aim at the Maritime Organisation’s (IMO) 2020 sulphur cap and has installed exhaust scrubber towers on more than 100 vessels.

When he established TECO 2030 it was, as its name suggests, with the year 2030 in mind. That is the target year for the IMO’s 40% carbon intensity reduction for shipping.

In March 2021, TECO 2030 announced it is building Norway’s first large-scale hydrogen fuel cell factory in the northern Norwegian city of Narvik, and is on schedule for production to start up in the fourth quarter next year.

There will not be large-scale fuel cell production for maritime applications until 2024, Enger says, and everything else to date has been negligible.

He lists a few companies involved with fuel cells – Ballard, PowerCell, NedStack – but says these are mostly working towards the automobile industry, with fuel cells for cars and trucks, not the big systems needed to power ocean-going ships.

The Narvik plant will eventually have a production capacity of more than 1 gigawatts/year and primarily produce hydrogen fuel cells for ships. The fuel cells will convert hydrogen to electroactivity to power ships, emitting only hot air and vapor in the process.

These fuel cells will first be made to power ships while they are loading or unloading cargo in port, and on shorter voyages along coasts or between larger cities. Enger points to the UK, Baltic Sea and Norway’s west coast and fjords as areas for near-term deployment of ships running on fuel cells.

When zero-emission regulations kick into effect for Norwegian fjords in 2026, cruise liners either have to retrofit existing ships or build new ones to run on zero-carbon fuels.

But beyond short-sea shipping, current fuel cell technology is not quite there yet to power larger ocean-going ships. For that to happen, today’s proton-exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells will have to make way for the next generation of solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs).

Individual SOFCs are similar to PEM fuel cells in size, but larger when assembled together. SOFCs have higher energy efficiency compared to several other power sources. While PEM fuel cell systems can be suitable for short-sea vessel voyages and for larger vessels during port operations, SOFCs will likely be needed to power some of the bigger vessels over greater distances.

Fuel cells technology is only set to properly mature to power larger 30,000-50,000 dwt ships by 2028 at the earliest, says Enger. He believes that fuel cells will then be ready to bring vessels across the Atlantic.

On the demand side, Enger thinks the pressure on shipowners to curb emissions will only grow. We could move towards a market where vessels with better emissions ratings will get cargo deals first, he predicts.

But while IMO 2020 kicked into effect overnight, the green transition for shipping will be more gradual. The IMO currently has a target of 50% greenhouse gas reduction by 2050, which its members agreed on in an initial strategy back in 2018. The strategy is up for revision next summer.

Not everyone in shipping is concerned about emissions beyond being compliant with upcoming regulations, Enger points out, but TECO 2030 has seen a big boost in attention and is in talks with more than 100 industry players.

By Erik Hoffmann

Please get in touch with comments or additional info to news@engine.online